“It’s probably the longest road of any game design I’ve had in play”: COIN series designer Volko Ruhnke talks new game Hunt for Blackbeard, solving the hidden information conundrum, and why he’s moving on from the series he created

Crafting a game system so compelling that other designers want to create their own games using it is a rare beast in board gaming. Veteran wargame designer Volko Ruhnke has managed it twice – first with the COIN series, which saw its asymmetric counterinsurgency design influence games including Root, and his Levy and Campaign series, which currently runs to nine volumes of designs by various creators. The former CIA intelligence analyst spoke to BoardGameWire about his continuing drive towards accessibility with new design Hunt for Blackbeard, which is on Kickstarter now, how he’s solving the hidden movement mechanics conundrum, and which games have been influencing his own design processes in recent years.

(Disclosure: Kevin Bertram from Fort Circle Games was an early financial supporter of BoardGameWire in February 2024. BoardGameWire is fiercely independent in its reporting, and that support had no impact on us deciding to interview Volko, who as a major figure in board game design we obviously would have jumped at the chance to speak with regardless. But we include this here in order to provide complete transparency.)

BoardGameWire: A decade ago you were interviewed by the Washington Post [about your designs], and you said, “I most definitely want to interest board gamers from all traditions in meaningful topics like insurgency. Fun and accessibility are a big part of getting them there.” How has that ambition held up over the last decade, and how has your design philosophy changed over time?

Volko Ruhnke: “So that ambition absolutely remains central to me. I’m very excited by cross pollination, synthesis, bridges between tribes – any kind of fusion. I find fusion food, or fusion music, tends to produce something even cooler. And, in fact, we know, that’s how all technological innovation, and I think art and music as well, happens: by diverse things being combined in new ways to new purposes with new twists. It was an English journalist, Matthew Ridley, who said, ‘all innovation is ideas having sex’. So I’m very much of that view with regard to board game design. And so over those ten years I’ve been involved in other efforts, including the Zenobia Awards, for example, that seek to broaden the participation, not just of players, but designers. You end up then with much more diversity in the exciting range of topics being designed.

And serious topics, I remain focused on that as well, because I am mainly interested in history, real human affairs. I mean, I’m a science fiction guy and fantasy guy too. But in particular history, and how things really worked in specific places and times in the world interested me and, well, a lot of those topics are very serious. Ten years ago I was around Volume Three of the COIN series, Afghanistan, and obviously its a very serious topic, insurgency in Afghanistan, that I worked on with Brian Train. It might seem like, ‘Wow, what would be fun about that?’ Especially when that war is still is still going on. And for me, I guess learning is fun. Examination, exploration of history is fun, time tourism is a big part of the fun for me in games. And so if the game is on a serious topic, consequential topic, where there’s something to learn that really matters to us, to our history, and to where we are now and where we’re going to, how human beings live and interact… and the way that we engage with that is at the same time, respectful to how we think things really were, you know? It’s not a whitewash, it’s not fanciful. It’s not intentionally skewed – everybody has biases, and I do too, but it’s not seeking to skew the picture. It’s respectful to the history, but at the same time, is fun to play, is engaging. That’s exactly where I want to be.

Did you ever think there would be a market for a COIN game when you began designing your first one? Did you think ‘Oh, there are people who are gonna love this’, or were you designing it because it’s something you wanted to play?

I did work hard to give it every chance that people would love it, and of there being as broad an audience as possible. And so the COIN series, as I was implying in that statement that you quoted, I intended by design to draw in people to this kind of game, this kind of topic, who might not otherwise have come to it. And ahead of time? No, we didn’t know what the COIN series would become.

Within my own little corner of the hobby, which was historical board games, war games specifically – military history – it was niche within that, because we were so traditionalist: there’s World War Two, and there’s Napoleonics, and there’s American Civil War and a few other things, and that’s it. Like, that’s all of history! [laughs] And in fact most of the wars were not conventional wars like that, most of the wars are internal wars, or insurgencies or guerrilla wars, and that sort of thing. And so I was trying to just broaden within my slice of things what we might play. But I also wanted to lure folks who might not be interested at all in military history, and might be more interested in, don’t know, agriculture, or fantasy topics or whatever, to see something familiar, at least in look and feel and style in the COIN series games. And then I was hoping they would find out, you know, ‘turns out insurgency in Colombia is really a fascinating story’, and there are fascinating characters there, and makes them want to learn more.

But we didn’t know. Gene Billingsley, the president of GMT Games – I had done Labyrinth: The War on Terror for him, that was sort of his commission, and his idea, and it had done well. And so I said, ‘Okay, now it’s my turn. Gene, I want to do insurgency in Colombia’, and he was like, ‘Oh, no, I can’t sell that [laughs], insurgency in Colombia – I can’t sell that’. But I said, ‘But it’s gonna be a series’ and he was like ‘Okay, that’s a little better’. And you’re going to be able to play it solitaire as if you’re playing against three other people. And it’s going to have, relative to board wargames, relative to GMT products, relatively accessible rules, and play aids and tutorials. And it’s not going to have little paper markers with bunches of numbers on them, and not big combat results tables that you have to cross-index and add four or five die roll modifiers to find out what happens every time you fight. It’s going to have wooden bits, area movement, and basically all the actions everybody can do on a single piece of paper – or more or less.

So all of that was because I thought ‘I am going to have to pull out every trick I know to interest people in insurgency and counterinsurgency in Colombia’. And it took a long time – it did not do well in GMT’s P500 system, Volume One of the COIN series. It took a long time to convince folks that this might be a fun thing to own and play. And here we are: it turns out that, I think, it succeeded beyond my ambitions, particularly because my original vision for the series was way off from what it ended up becoming. I had an idea of doing one moderate insurgency on each of four continents, and just me as the designer. Well, that never happened – from Volume Two on it’s other designers coming in and doing new things that I couldn’t have envisioned. So that’s the thing I’m most proud of, is the COIN series attracted talent to the form, and to that type of topic. Now we have folks like Steven Rangazas with The British Way and The Guerrilla Generation, who knows much more about insurgency and counterinsurgency than I did at the time. He’s an academic, studying it at the postgraduate level. So that was the key to the success – it drew in not just players, but designers and creators too.

It must feel pretty wonderful to have created this this system which other designers have hooked on to and realized, ‘ah, I can do something with this, I’ve got an idea, I understand how I can map my personal interest onto that’, and make something, hopefully, equally as interesting as the games you’ve come up with?

Absolutely. I mean, that’s something I think we all want, don’t we? To influence the state of the art. So it is quite a joy. If I think about my designs as my children, I have grandchildren and grandnephews now and there’s a spin off series from GMT called Irregular Conflicts Series, which is ‘COIN adjacent’ is the phrase they have for that. So I’ve actually created something to which it is worthwhile to be adjacent to. That’s pretty cool.

What’s your take on games like Cole Wehrle’s Root, which don’t have a huge similarity in terms of the historical nature of the games, but certainly bear an inspiration from your system?

Yeah, and Cole Wehrle, the designer of Root, has affirmed that. And yes, I think that’s fantastic, because Cole is such an insightful and talented designer, who also I think has that idea we were talking about, you know: being very serious about what his game designs do with regard to one’s perspective on the setting on history. He’s talked a lot about John Company, and what it has to say about the British Empire and how empires work, and how empires understand themselves. He’s an extremely thoughtful mind, and with Root, he’s put the dynamics of insurgency, and counterinsurgency, and politics into a package that so many people can find engaging, rather than off putting.

I’ve read many times folks who come to Root, and then they go from Root to something else that might be similar. And I think that’s what’s been happening the last 20 years or so in board games. Rather than our electronic connectivity replacing manual games, replacing things on our table, they’ve enabled us to find each other and to find other games and to get out of our little niches and corners of the hobby and find other things that might excite us. Games like Root are so instrumental in that because they take from one part of our community and bring us to other parts of our hobby, they bind us together and allow us to reach across tribes. I love that.

When you’re designing the games how much weight do you ascribe to, ‘this is what we know happened in the conflict – so this is how I have to design the game to broadly push players in that direction’. How much of your game design is giving people the tools so anything can happen, and how much of it is locked in?

The question of how much we depart from history is a design question. It can’t be zero. It’s not a game, if you give the players no agency to depart from history. But if it departs too from much from history, then it loses plausibility, and you’re not actually transporting players to that time in place. And that’s not a bright line, right? That’s a that’s a decision, how alternative shall we let the history go? I go about that kind of in the opposite way – I don’t look at ‘where should it end up, and then how do I build towards that?’, but I start with the strategy that the ends, ways and means try to replicate that, try to replicate the environment, the key dynamics that drove things.

In history, I’m a little bit less interested in what happened in the end than how did it work? And I feel like games can explore that in a way that few other tools can. But I have to compare the model’s outputs to what did happen, because it needs to fit into that plausible area. Here’s a trick, and it’s very well explained by Professor Phil Sabin, who used to be at King’s College, and has a great book, Simulating War. And he says, when we’re looking at the outcome of military conflicts, they’re all kind of a bell curve, right? And there are some things that happen that are very unusual, that are extreme that are low probability, high impact events – and we can’t really prove that we now know exactly where in the bell curve things ended up. Maybe it’s right in the middle of the hump, the expected result, and maybe it’s way out on the tail.

Well, a game design makes an argument of what that bell curve is, with the outcome of the game. So if we played this game 1,000 times, what will it produce? And the historical outcome doesn’t have to be in the middle of that curve. Right? You can validly argue in a game that the historical thing is almost never going to happen, because it was very, very unusual. Now, you’d better do that consciously and explain that. But that’s the choice you have as a designer. You don’t have to have the result of 1,000 plays, and always end up clustered around the historical outcome to have a valid historical model.

We talked about your ambition for having fun and accessibility as a design philosophy, even with the COIN games. Your new game Hunt for Blackbeard is on the lighter end of things, and seems more accessible than some of the other games you’ve designed. Was that an intentional shift for you?

It was an intention – I wanted to be successful in having a game that would tend to play out in 45 minutes or less. And that guides how much you focus in on the key dynamics and the key elements – how much you simplify in effect. And I thought that this story could be told in that format. Also, the way I wrote the rules, the way I did the Learn to Play [guide], the way the components look: I’m trying to learn and change and kind of get out of my zone, you know? I do have a sort of a natural, maybe a 20 to 30-page rulebook kind of zone that I seem to work in. But yeah, here I did try to see how quick and simple could I make the game to still get at the key dynamics of man hunting.

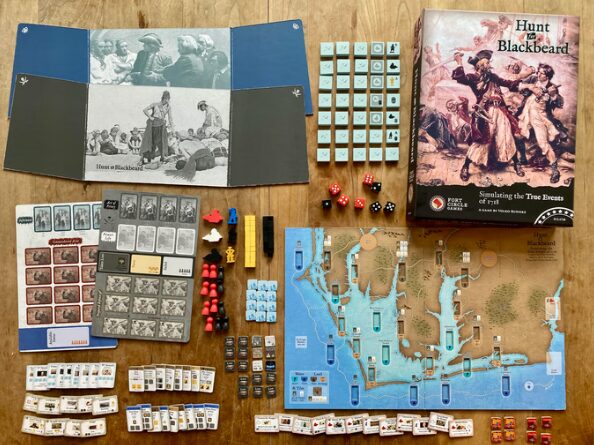

And the particular story of that hunt for pirates in 1718, there are certain things I did want to have in that. And, and so this is what I ended up and it’s, you know, I’d be happy if it were more accessible. There are some intricate aspects to Hunt for Blackbeard, despite the fact that the board is small – there are only 24 main spaces, really – and it will play in I think, 15 to 45 minutes once you know how to play. But there are intricate aspects to what each player is doing, that you have to learn. I wish that would be even easier than it is, but it’s the best I could do, and still deliver the story that I wanted.

My experience of learning and playing different wargames is that, as you say, these can be quite large ‘wall of text’ rule books. But as time has gone on the player aids, and the help sheets, and inclusion of step-by-step tutorial turns are getting better and better. Is that something you’ve learned over time, or has that been inspired from elsewhere?

Well, I am definitely trying to learn, I try to do a better design each time and that includes how the rules are communicated specifically, in this case, this is GMT and I would say specific other people. And this goes back to my pride in a series like the COIN series attracting other talent. So from the beginning, with Volume One, Andean Abyss, my developer Joel Toppen had great ideas about how to make the board easier to use, how to make the play aids easier to use, and especially to write a tutorial in the playbook – I never would have done it that way. And now of course we have folks making videos and writing articles and other media to help us into these games, and that’s really the magic that has continued. More people have become involved with the COIN series and now the Irregular Conflict series to push the state of the art forward, in helping you into the game.

And so I mimic that, you know – that’s the case with Hunt for Blackbeard with the learn to play booklet. It also has a ‘teaching teaching’ aid, a section on ‘Okay, now you’ve learned to play the game, but you want to teach others. Here’s a step by step process,. I got that idea from Joe Dewhurst and Fred Serval and what they’re doing for GMT, and tried to execute it in my own way. My even more recent design, Coast Watchers, is with GMT, and it has a completely different style rulebook from the COIN series, from the Levy and Campaign series, and even from hunt for Blackbeard. It’s a rulebook that I tried to mimic the style of a designer I respect very much, Jerry White, and his game Atlantic Chase. He has sort of a unique style there that was very well received, and I had gotten to the point with Levy and Campaign that I was not happy with how players were reacting to the way the rules were written, which they found was getting in the way. I’m used to a certain style [of rulebook] from 1975, you know, and, that’s just kind of where I start out and what makes sense to me. But technology moves forward, and we’ve made progress in 50 years, and so I’m trying to catch up as best I can.

What would you say, mechanics wise, are you most proud of with Hunt for Blackbeard?

It’s actually a decades old problem in board games of how you do hidden information and reconnaissance, or intelligence gathering, that I think hunt for Black Beard solves. The problem is that when we have a hidden location, the enemy knows where their forces are and we know, there’s a lot of ways we have – screens, written notes, inverted counters or blocks with a lot of dummies. But the problem was: let’s say it’s a naval situation and I search for you, and I call out square B36. Are you in square B36? Because I’ve got a reconnaissance plane flying there, or a frigate’s gone there or something. And you say, Yes. B36 has a fleet in it. Okay. So now, I know where that fleet is. And you know that I know where that fleet is, by the nature of the mechanics. And you know more than that – you know that I had search assets in range to search there, even if you weren’t there. Maybe you’re nowhere near B36. But because I call that out, I had a search asset that could reach that, and now you know something about my location, even though you’re not anywhere on the scene.

Now, in real life it often came about that I found out something about you, and you don’t know I found that out – that’s a key information advantage that I have. Well, that’s very true in intelligence work, it’s true in reconnaissance. So in Hunt for Blackbeard, for example, the pirate hunters, the Royal Navy and the Virginians, they’re using a lot of informants – people where Blackbeard is in North Carolina, that while North Carolina is a friendly place for him, a sanctuary, there are people there who don’t like him being there and are informing on him, are spying on him. And historically, Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Spottswood used a lot of these informants, these spies to gather information on Blackbeard, so that when he financed the Royal Navy expedition into North Carolina – into hostile territory, in effect – they already had a lot of knowledge of Blackbeard’s activity, his likely whereabouts and activities. So that’s a big part of the game.

But historically, Blackbeard didn’t know that. He was being warned, probably, but he didn’t take seriously that threat. And when the Royal Navy showed up at his anchorage, he was taken by surprise. And that plays a big role in in catching in defeating him. So that has to happen in the game. So how do I do that? Hunt for Blackbeard uses blocks. Most wargames that use blocks, the blocks are forces, right? It represents a unit. It might be a big unit, a small unit, but you don’t know what it is, you don’t how strong it is, but you know that there’s a unit there or it’s a dummy. And you see these things moving across the map, right? In Hunt for Blackbeard the blocks actually information about these 24 locations in North Carolina. And what the block show is, there’s either pirates there of some kind, or nothing. And here’s a twist. For the, for the hunters to use their informants, what they’re doing is they’re inspecting selectively those blocks. And to do it secretly, it’s simply you ask the opponent briefly to close their eyes. You look at the block, or you change it out if you’re the pirates moving around. Okay, I’m done. Open your eyes. Very simple.

But now every time it’s time for the hunters player to tap their informants – the informants are tiles behind the screen, using pawns for actions. Every time that happens, the hunters player might or might not be finding out key information about Blackbeard. They might be finding out negative information, where Blackbeard isn’t, or they might not have tapped any informants at all. That entire process is, I think, handily hidden from the target of the, of the collection of the intelligence collection.

We also provide a little planning map that shows you the geography, and your opponent won’t be able to see what you’re particularly interested in. It’s a small game, there aren’t that many blocks, you know, there’s one pirate ship, right? It’s quite handleable. Ask them to close their eyes, do your thing, which takes a second or two, and then release them, you know, say ‘I’m done’. But it works, and we have the virtue of, for what’s on the short side of playtime for my designs, we’ve been able to play it a lot over the years. So it works.

What was the process for making Hunt for Blackbeard a reality? How long ago did you have the initial idea? Where did it spring from? And did you pitch it to Fort Circle before anyone else?

It’s probably the longest road of any game design I’ve had in play. It actually started way back when I still had my day job as an intelligence instructor. I teamed up with an expert in analytic support to the hunt for fugitives from the law. So we did a classroom training game called Kingpin: The Hunt for El Chapo, set in modern Mexico, that was intended to show the dynamics of that endeavor. And from that classroom game design and teaching experience, I thought ‘I can make a commercial game in a historical setting’, and I started thinking like, what were some key manhunts that I might feature. And when I read the story of Blackbeard in North Carolina and 1718, I said, ‘Well, this has the elements I’m looking for’ – the dynamics of man hunting and intelligence collection, and equipping an expedition, and a well-defended target – and going into kind of hostile ground to capture him.

They caught up with Blackbeard at the Battle of Ocracoke, in November 1718. And I wanted to have this game going to print on the 300th anniversary in 2018. That did not happen clearly [laughs]. So that’s how long I’ve been working on it. We went through a pre-order process with GMT in an earlier version of the game that showed us that the market, at least for GMT’s audience, was not there, and there were a number of reasons for that. But one that GMT thought was that it did not have a solitaire version. So we worked – I say we, it was mainly me, but there were certainly others involved – for about two years, trying to make that happen. I designed some solitaire systems. I did not like them. And the playtesters were lukewarm on them, I’d say. And so I finally gave up on that. I don’t think the nature of this particular cat and mouse game… I don’t know how to make it fun for one player.

At that point it became clear that GMT was not the right home for it, even though in the meantime we had improved the game a lot for two players as well. It was just going to be a challenge, I think, to go through their preorder system. And I knew Kevin Bertram from Fort Circle games, he’s local to me, we’re friends, we’ve played together a lot. And I said, ‘I have a game that’s looking for a publisher’. And you know, his first game on the Shores of Tripoli has pirates in it [laughs]. And Hunt for Blackbeard was small and accessible enough, and has components similar enough to fit his line, and he was okay with this being a two player game – let’s have a great two player game instead of offering a mediocre solitaire experience, or doing nothing at all and just not printing it.

He liked it, test played it with Jason Matthews, Twilight Struggle designer who’s also local here. They liked it and so he agreed to back it, it’s on Kickstarter now. And now we have the art from my friend and professional artist and also game designer Marc Rodrigue. So I’m very happy with where we’ve ended up.

What tips have you got for designers who are thinking, ‘Oh, maybe I’d like to pitch towards a historical Wargaming publisher like GMT’. What advice have you got for people looking to get in on that space?

I think even with all of the media that we have, and the communications, everything, we are still talking about a lot of small companies – not all wargame companies are small – but mostly small companies, family affairs in some cases, and it’s still a very tribal kind of community, despite all of our efforts to bridge that and cross pollinate. So just knowing people just matters a great deal. And so being out there, engaging with people, playing with people, helping others with their games. When I pitched my first design to GMT, a quarter century ago, I had already been quite active in playtesting their games. And I knew a number of their designers personally – the first time I met the president of the company, it was at a game convention, and I went with him to his hotel room to shrink wrap copies of a game that had just come in, you know, and I’m just helping him assemble these games. And that was some years before I pitched the first game to GMT. So one aspect of the success was that, that I knew them and they knew me. And people they trusted and had already worked with knew me.

The second key element was it wasn’t just me saying, ‘Hey, I’ve got this game, and it’s fun’, because they’re immediately their question was ‘Who else thinks it’s fun?’ And so then when I said, ‘Well,

Rob Winslow he thinks it’s fun’. So they go and ask Rob Winslow “So we saw that you played this, what did you think?’ And Rob said, ‘Yeah, I liked it’, and they said, ‘Do you like it enough to be the developer?’ because they knew him, as a tester, and as just a personality out there playing and commenting on games. And if he had said no I don’t know what would have happened. But it was quite the test there, you know, of commitment. He said he would develop it and GMT said ‘Okay, then we’ll take it, because Rob believed in it’. So that’s a network, and that comes from being out there engaging with people and specifically whatever it is that constellation is around that particular publisher that you have in mind. Because it’s different, we’re lots of little communities with ties between them.

If you could go back and speak to the Volko designing Wilderness War, back in 2001, knowing what you know now – what would be the key advice you took to him?

I was much more hesitant then to break the mold on what had been done before. I don’t know that that was necessarily a bad thing, because I think Wilderness War was a game that was familiar to somebody who had played Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage or Paths of Glory – familiarity is good. On the other hand – I mentioned Marc Rodrigue, who’s doing art for Hunt for Blackbeard – his design Bayonets and Tomahawks is the same setting as Wilderness War, but further down the board game technology pike. If you play those two games, you’ll just see the role for innovation and looking at a conflict in a new and, I think, more effective way.

So maybe I might have said, you know, don’t worry so much about changing what Mark Simonich and Ted Racier did before. But I got there, you know? I think with each with each design, I got a little more courageous and solved the problem in a new different way. And now that’s what makes me mostly excited, anyway. For Wilderness War the concept, the game was Hannibal, Rome versus Carthage, but it’s the French and Indian War. What would that look like? And for Labyrinth, it’s Twilight Struggle, but it’s the global conflict with jihadism. What does that look like? And I think by the time we get to the COIN series, we’ve got some really cool work in gaming insurgency and counterinsurgency from Joe Miranda and Brian Train and a few others, but nothing that is of this kind of broad appeal. And when I say broad [laughs], I mean, relatively, within the historical board gaming community. How could we do that, based on my accumulated kit boxes of tools of mechanics that I’ve seen and other ideas I might have? So I think I’ve gotten there, and I think that journey, maybe was all for the best. So I don’t know what I would say.

Maybe you have to go through that process, I guess? You learn the rules before you can break the rules.

Exactly. I think so.

What game have you been most impressed by, or has most influenced your design over the last year or so – has anything really jumped out?

Atlantic Chase certainly, clearly, the way that that is presented was a huge, huge influence since I tried to copy that kind of approach [laughs], you know, in my own voice, but tried to try to mimic that approach. And the last year is a short time. I mentioned Coast Watchers, which is a current GMT P500. There’s sort of a Volume Two in that series if it becomes a series, which is set in the Battle of Verdun in 1916. And it’s about reconnaissance, specifically, in Verdun, so it has its own focus. But there’s a Verdun battle game called Verdun 1916: Steel Inferno by Fellowship Of Simulations, Walter Vejdovsky, from about four years ago – it’s just amazing in giving you the flow of the battle in a beautiful and accessible way, and also drawing in the larger strategic environment in which the battle took place with playing cards.

So that one, not with regard necessarily to any specific mechanic, but in kind of giving me: what are the dynamics of that battle? How did it flow, that kind of thing. It was very influential, even after having read, like, the classic Price of Glory by Alistair Horne. It’s not that I didn’t know anything about the Battle of Verdun. It’s just when you play the game, and you have that agency and you’re operating a machine yourself, you see it in a more vivid way and, and Steel Inferno from Walter did that for me for Verdun. So that’s one. I’ve just recently played only twice another World War I game called Downfall of Empires by Doit games. I think it’s a year or two old, it uses what look like very basic counters for forces and trenches, and a few technology tiles, and a very basic sequence of play, and extremely basic combat and supply rules to deliver a really compelling development of the Great War in Europe. That’s one where I’m like, ‘Okay, this was much better than I expected to be when I first looked at it’, because it looks so simple, it looks simplistic, but it’s not. I haven’t yet drawn anything from that, because I have to study it longer. It’s going to take me another probably couple of years [laughs] to figure out: ‘How did they do that? And is there a way that I could I use that in a future design?’ Because I just admire the accessibility of a design that delivers both vivid and valid history.

Are you done with designing COIN and Levy and Campaign games now, or do you think you’ll go back to them?

I won’t be designing any more myself, and a part of that is that I’ve moved on to now experimenting, very much with hunt for Blackbeard, and with Coast Watchers, and with the Verdun game, with hidden information mechanics that help encourage denial and deception as an aspect of gameplay and of history. So that’s kind of the area I’m focused on as a designer. That’s one reason, but another reason is that neither the COIN series nor Levy and Campaign needs me, at least not as a designer. To still be supporting it? Absolutely, and I’m still active with Levy and Campaign designers in particular. But they are doing very well without me [laughs], to the point that: there’s a queue, right? There’s only so many games that the market can take in of a particular flavor that GMT wants to offer on preorder because if it’s too many, there’s just a fratricide and it’s clogging the system. And that GMT can produce in a year, you know, there’s a certain speed there. And we have a queue of games in Levy & Campaign, we have beyond 10 volumes of designers and projects working, and really the question is not ‘what are we going to find to be volume eight?’, it’s ‘Of the candidates, which one is most ready to go as volume eight?’

If I then step in and say I’m going to do one now too, it just pushes that queue further down, and that’s not fair to other designers, even if I was inclined to do another. So I’ve said what I’ve had to say, and now others have improved on that and taken it in new directions. For Levy and Campaign, Plantagenet – it’s a War of the Roses title, Volume Four, by Spanish designer Paco Gradaille, seems to be getting a stronger reception than any previous volume by me, so again, I would just be a kind of an anchor, I think.

Hunt for Blackbeard’s Kickstarter campaign runs until Sunday, June 30 at 6.30pm.

[…] https://boardgamewire.com/index.php/2024/06/28/its-probably-the-longest-road-of-any-game-design-ive-… […]

Working with Volko on A Distant Plain will remain one of the highlights of my design career (or careen, as the case may be).

Ave!

[…] leading the Zenobia Award process himself, alongside a board of industry professionals including COIN series designer Volko Ruhnke, BoardGameGeek writer and podcaster Candice Harris and former Netrunner lead designer Damon […]

[…] leading the Zenobia Award process himself, alongside a board of industry professionals including COIN series designer Volko Ruhnke, BoardGameGeek writer and podcaster Candice Harris and former Netrunner lead designer Damon […]