“It’s not uncommon for me to revise parts of the game as many as 15 to 20 times”: Descent, Arkham Horror design veteran Kevin Wilson dives into worker placement for his third Kinfire game

Kevin Wilson barely needs an introduction when it comes to the modern board games industry, having spent more than 20 years working across titles ranging from Descent: Journeys in the Dark and Arkham Horror to Cosmic Encounter and Civilization: The Board Game. Since being named director of game design at Incredible Dream upon the company’s 2021 launch, he’s been the design lead on a trio of games in the new Kinfire setting. The latest, Kinfire Council, sees Wilson bringing his own take on the worker placement genre – and is just about to complete a successful Kickstarter campaign. Wilson sat down with BoardGameWire to talk worldbuilding, prototyping, and best practice for designing as part of a team.

What was the initial inspiration for Kinfire Council – can you recall when you first started noting down ideas for the game?

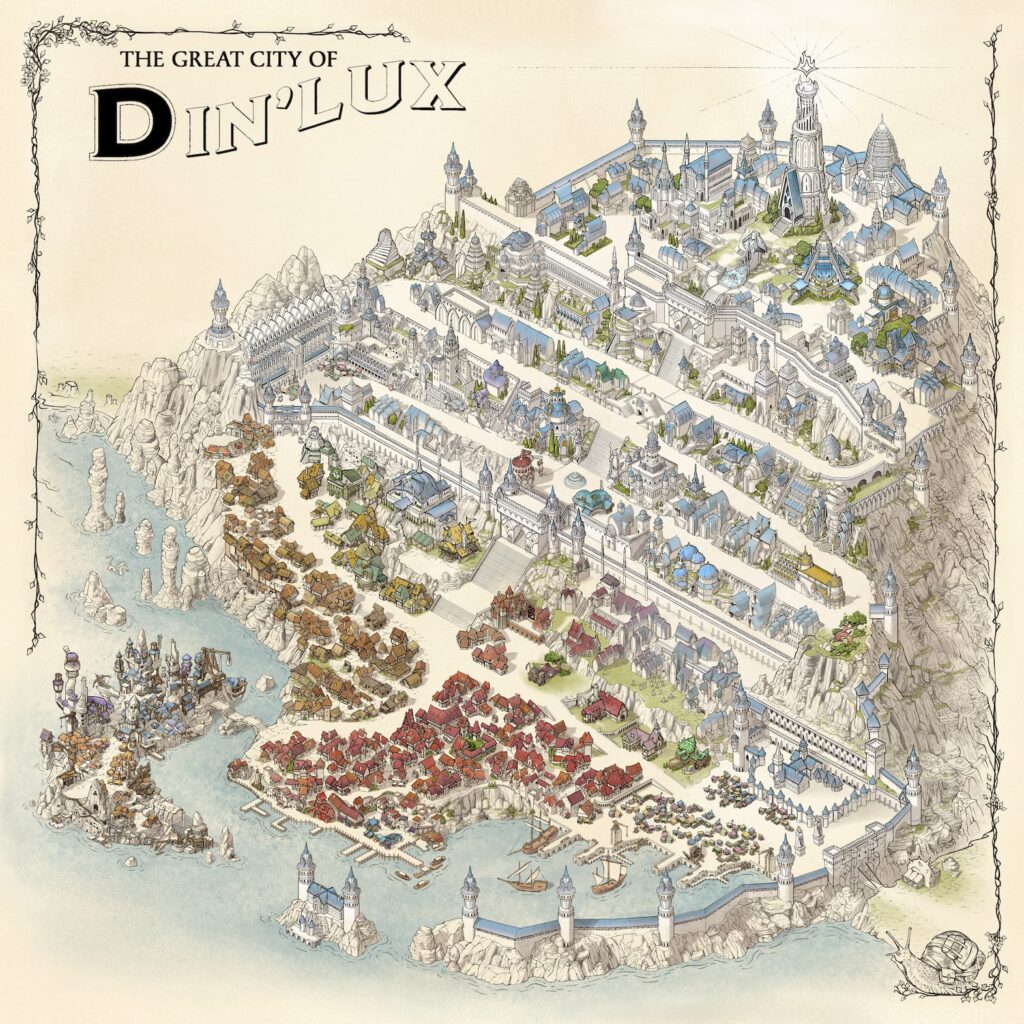

I knew I wanted to do a game set in the city of Din’Lux the moment our art team handed me the map they’d drawn for Kinfire Chronicles. It was so far past my expectations that I immediately wanted to set a game in it, and I started thinking about what kind of designs would make the most sense, eventually settling on Kinfire Council.

Worker placement with upgradeable workers is an interesting mechanic – is that something you’d been tinkering with for a while, or was that a fresh idea for Council?

Before sitting down to do Council, I hadn’t really messed much with worker placement design, but when I did my deep research dive, upgradeability was one of the things that I decided I wanted to include. I have a deep love for player powers and customization during play, so I knew I wanted to lean into that.

What have been the biggest changes you made to the game during development, and why?

Well, every mechanic has changed at least a little bit during development, but probably the lighthouse mechanic has had the most and the largest changes. Originally, the game continued until a certain number of kinfire lighthouses (one of the main driving goals of the game) were built. Ultimately, this made the duration too swingy, and it cut the knees out from under the investment strategies that take a bit more time to mature.

Did playtesting reveal anything that worked particularly well, or that needed reassessing?

Oh yeah, while the overall flow of the game has always been pretty good, some of the specific details such as the councillor player powers have been a struggle to nail down. But really, in a given design, if I’ve got the time, it’s not uncommon for me to revise parts of the game as many as 15 to 20 times to various degrees. Some game elements are essential to my personal design aesthetics, and I’m very fussy with them, while others may re-use well-worn mechanics that don’t need a lot of attention from me. It’s all about using your design and development time wisely.

Incredible Dream’s playtesting is mostly virtual, I believe – something that’s becoming much more prevalent across the industry. Has that grown out from the pandemic, and has it changed how you approach playtesting and design in any ways? And does in-person playtesting still have a place in modern board game design?

Incredible Dream started during the pandemic as a virtual office, so we were doing digital testing from the very start. While I do prefer in-person testing for the ability to watch body language and such, I’ve found that we’ve been able to manage okay, considering that our staff is broadly scattered around the world. Basically, I’d say use whatever tools you have available to fit your needs.

Kinfire Delve, Kinfire Chronicles and now Kinfire Council have all appeared in quite a short space of time. Did you bring any of these ideas to Incredible Dream when you started working for them, or were they all designed from the ground up after joining?

All of the Kinfire designs were created after I joined Incredible Dream. We spent a good chunk of time designing and developing Chronicles, since it was by far the biggest of the games, and also included a lot of the initial worldbuilding. Delve was a smaller, simpler game, and I was able to put it together fairly quickly, and Council’s been somewhere in the middle so far. I’ve got a lot of experience working under tight deadlines in tabletop, and our schedule has actually been pretty generous by my standards.

All three Kinfire games so far have very different play styles within a shared setting. Is that something you’re keen to continue with your next designs, or is it more likely we’ll see sequels / expansions / iterations on any of these three games next?

I personally enjoy the variety I’ve been able to bring to the table with Kinfire. I honestly get bored easily, so it’s been nice to do something new with each project. Will that continue? It’s hard to say, and will depend on how public response develops over time, what opportunities open up to us as a company, and what our sales numbers look like. As for what we’re doing next, I couldn’t really say yet.

You previously worked on games with strongly developed settings, such as Descent and Arkham Horror. How did it feel making the jump to Kinfire, where in addition to the game mechanics you’re involved in developing the setting from the ground up?

Actually, I’ve had some significant past experience in setting design. I was heavily involved in creating the 7th Sea RPG setting, the Spycraft RPG setting, and Android was largely initially my brain child along with Daniel Clark, so being involved in the narrative design as well is nothing new really. The main thing is simply to keep in mind your IP goals, whatever they may be, and balance those out with the other goals you have.

Related to the last question – how does the development of Kinfire work? Do you bring ideas and associated design mechanics to the story and art teams, do they provide ideas for you to turn into gameplay, or somewhere between the two?

We try to keep Kinfire as a fairly open collaboration between the team members. Each of us has areas that we’re ultimately in charge of, but feedback from everyone else is accepted and appreciated. I try to keep my art and narrative needs simple so that the other members of the team can shine and enjoy the process as well. Nobody wants to be treated as just an extra pair of hands – that’s not why people go into creative professions. And honestly, the rest of the team constantly comes up with cool stuff that I wouldn’t have thought of by myself. Flickers, the little mothling sidekick of Khor, our Revenant Tank character, was entirely a creation of the art team, and when they showed him to me, I was instantly sold and started figuring out how to work him into Khor’s design. Similarly, when I asked for “corrupted stags” for the players to fight, I got back sort of owl-deer, and that was neat enough that we just decided that that’s what deer look like in the Kinfire setting.

How does the setup at Incredible Dream compare to your time at Fantasy Flight, in terms of the structure of which games get designed and how, how much freedom there is to develop and iterate, how much time you have to spend on individual games?

Well, I’m in a lot more senior position now, as Director of Game Design, so I have a lot more say over what we design and how we design it. Deadlines are always driven by money decisions in the end, but I’ve learned a lot more tricks to managing development time and controlling risk and bloat in game designs. Overall, the pace at Incredible Dream has been a lot healthier, though, and I’m thankful for that.

You’ve done a real mix of solo designs and collaborative efforts over your long career – which do you prefer, or does that hinge on who the co-designers are? What do you think is the most important thing for designers to bear in mind for successfully designing as part of a team?

Solo designs are easier, to me, but collaborations will take you to more unexpected places. I’ve learned a lot over the years working with different designers, but a good match on designer tastes and goals seems pretty vital to me for a successful collaboration. You may want to work with someone else, but if they bring incompatible expectations about the design, the process, or the timeline, you’re going to have a really hard time of it. You need to clearly set expectations up front and then stick to them, and I personally wouldn’t work on a project without deciding up front who has the final say on design elements. It’s just asking for trouble to not nail that sort of thing down right away.

You’re currently the sole game designer at Incredible Dream – is that likely to continue for the foreseeable future, or has there been talk of bringing in other designers, either on a full-time or contract basis?

I’ve had a few talented designers work under me off and on, such as Adela Kapuścińska, Brandon Perdue, and Darrell Hardy, but I’ve been the lead on most everything so far. I doubt we’ll be bringing anyone else on full-time any time soon unless something really blows up for us and lets us expand our product pipeline significantly.

I’ve seen you mention Eric Lang as an inspiration – he’s currently very focused on designs which sit in the ‘light family’ space, which bridge the gap between mass market and hobby. Is that an area of the hobby game space that appeals to you?

That’s more Eric’s space than mine. I don’t know that audience very well, and honestly I tend to design for my own tastes, which are a bit heavy for that crowd usually. And that’s not to be snobby about it or anything, the hobby audience simply has a wider library of internalized game mechanics, which makes it easier for them to get into a new game as long as they recognize part of the design.

What is it about Lang’s designs, from a fellow designer’s point of view, that you find most appealing or noteworthy?

Eric has a firm grasp on the core concept that fun is more important than any other element of a design. If he puts something into a game, it’s because it improves the experience, not because he feels like it needs to be there, and that’s a rare talent indeed.

I’ve also seen you say Cosmic Encounter is your favourite game to play that’s not your own design. Can you speak to what it is about the design of Cosmic, specifically, that makes it sing for you?

Variety. No other game out there delivers such an amazing variety of play experiences in as tidy a package as Cosmic Encounter. The central framework is incredibly malleable, and a lot of smart additions have been made to it over the years. It’s also the game that most solidified the concept and value of player powers for me, which as I mentioned, is one of my favorite things in games, again due to the variety that it helps to create. I crave novelty in my games, and if a game gets repetitive, I’m pretty much done with it.

Of your many designs over your career, which do you think is the most underrated / deserves more love from players, and why?

Hmm, I’d say most of my games have had a pretty good shake, but I was disappointed by the reception to my IDW X-Files boardgame. I was told it was largely going to be sold in book and comic stores and designed it appropriately, and folks were disappointed that it wasn’t another Arkham Horror when it wound up largely getting sold into hobby stores. That happens sometimes though when you have bad intel as a designer. A mismatch of audience and game can be devastating, and with the way online reviews work these days, there’s usually no coming back from it.

What advice do you have for first-time or early-career designers, trying to break into the modern hobby games industry? How have things changed for designers compared to when you began, or even in the last five years or so?

My advice is make games that make you happy. Don’t try to please other people in a vacuum. Just make things that you like at first. The market is incredibly saturated these days, with more games coming out at Gencon than would come out in an entire year when I first started. It takes a lot to break into the hobby now, and a couple of the few ways to get noticed are passion and originality. That said, don’t ignore other peoples’ advice, just keep a vision in your head of what it is that you want to make and always try to steer towards that. You may never wind up getting published, but at least you’ll make things that you can be proud of.

Kinfire Council’s Kickstarter campaign runs until May 28.