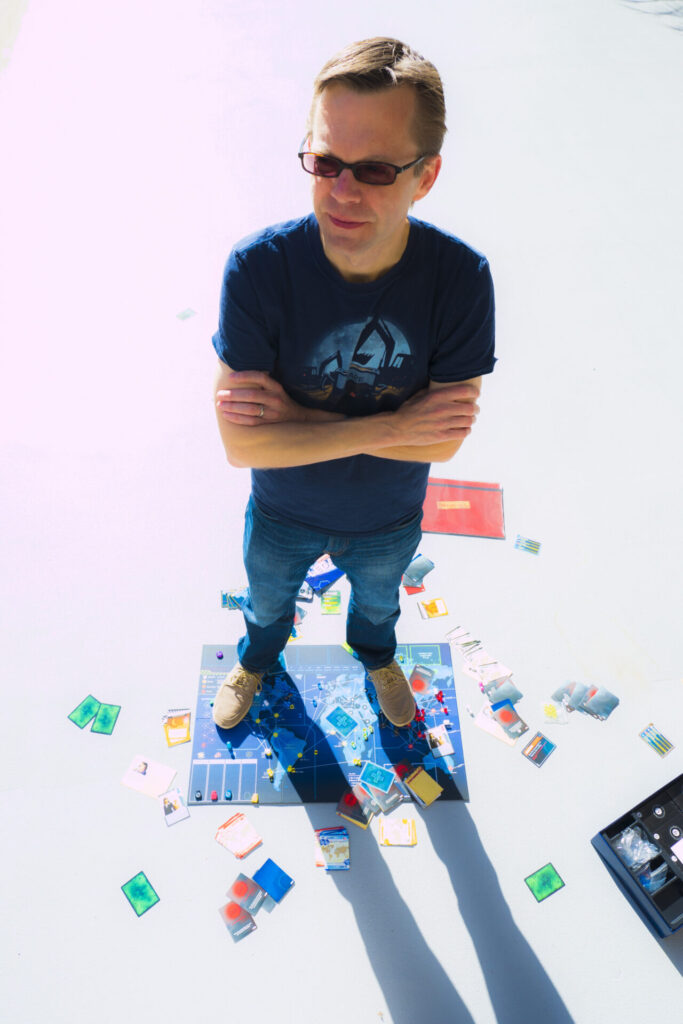

Pandemic creator Matt Leacock on fighting for designers’ rights, working with effective developers and his publisher ‘pet peeves’

After being catapulted into the board game industry limelight following the success of Pandemic in 2008, Matt Leacock has scored ongoing success through titles such as the Forbidden series, Ticket to Ride and Pandemic legacy titles and his Kennerspiel-winning climate-change co-design Daybreak. In this in-depth interview he spoke with BoardGameWire about how the industry has changed for designers over the last quarter of a century, how working with developers can best help a design to sing, and why fighting for designer rights is among his most important jobs in 2026.

BoardGameWire: It’s almost 20 years since Pandemic was first published. What do you think have been the biggest changes for board game designers, specifically, within that time?

Matt Leacock: Oh, let’s see. So a few things. There’s just so much more competition out there, so much more product. I think when I started it was a lot easier to get noticed. I mean, when I think back to 2000 when I really got started, and went to Spiel [Essen] and sold my little racing game, I didn’t need to have a whole lot, and the production value didn’t have to be that great. And it was just easier to get noticed, people would stop by.

And now, if I were to do the same thing, I’d get laughed out of the hall because, you know, I’d be competing with thousands of other products. But on the flip side I think there’s a lot more support for new designers, up and coming designers. I look at all the cons that have Protospiel events, and Unpub, and see a network of a lot of people who are helping each other out and kind of helping to pull each other up and share best practices and so on. So yeah, I guess I see some easier things and some harder things at the same time.

Do you think you were fortunate in terms of when you happened to start pitching designs, and began going to places like Spiel and shopping designs around?

Well, I do think it was easier to get noticed – but that said, the product still needed to be really good. So it took a long time: many, many years, before I had something that was, I think, worthy of being published. Like, I don’t even know how many years. I started working on my first design in college, and I spent, like ten years on it, and then it came out in 2000 and it was fine. And then it took another eight years before Pandemic came out. So yeah, it was perhaps easier to get noticed, but you still needed to have a something worth being played, and I think that’s still true.

How do you think Pandemic’s success changed your career path and choices – and is there anything you think didn’t change about how you were approaching being a game designer?

I mean, it changed everything. I was a hobbyist, and then I was somebody kind of doing it as a side gig a bit. And then Pandemic took off, and it just allowed me to step away from my day job and change careers completely – and that was not something I had planned on doing. It was just this wonderful opportunity. It did take a while, though. The game came out in 2008 and I started working full time 2014, so it took about six years before I was comfortable enough to switch.

And is that a factor of having to wait until it’s financially viable? What was it that persuaded you it was okay to take the jump?

Yeah. So I’m living in the San Francisco Bay area, like, in the heart of Silicon Valley, so the cost of living here is not low – and I’ve got two kids to put through college. And you’re basically getting paid a paycheck four times a year, and you don’t know what it’s going to be. So it took many quarters, years of seeing that this title was an evergreen and was going to be able to help meet the bills and so on. And once we saw that, then we were able to kind of shift.

How much of your design work in recent years is you going out and pitching to publishers, and how much is publishers coming to you?

Oh, yeah, the last few years, it’s been much more… I’m just really lucky in that I’m able to kind of pick and choose projects, and most of them are publishers coming to me and saying, ‘Hey, I’ve got an idea for something’. A lot of the work that I’m doing is expanding existing worlds that I’ve already built, whether it’s the Forbidden stuff or the Pandemic stuff.

So I’m lucky in that I’ve kind of got those two different playgrounds to play in already, but there’s very little of me, like, inventing from a totally blank sheet of paper. It’s generally someone pitching an idea – occasionally, like with Daybreak, I did have an idea, but then I also ran into another colleague, or someone who would become a colleague, and we worked on it together. And we had a publisher lined up maybe halfway through the process – much earlier than typical.

So I do like to have a relationship with a publisher fairly early on, and often it’s through a pitch. So I’m not doing a whole lot of cold calls or cold pitches.

You’ve worked with quite a few major and smaller publishers over the years. How consistent is what publishers ask of you, in terms of initial design and development and final production, and do you think any of those approaches work better than others?

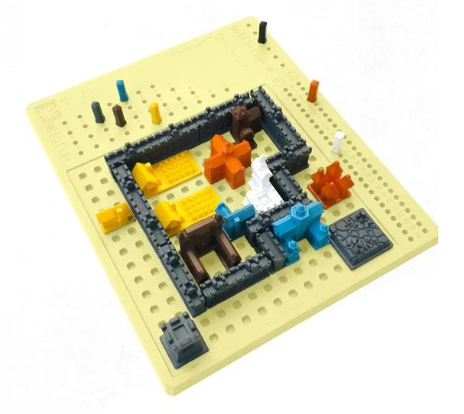

Yeah, I would say that it is all over the board. So a case in point: I worked with Studio Big Games, Z-Man – part of Asmodee – on Fate of the Fellowship. And that was just a really tight collaboration, with in-house development, creative direction, art direction, sculpting, you name it, down the line – a really great, expanded professional team. I worked with Kevin Ellenburg on development there, and he devoted almost a year to internal development, really working with me to refine the systems in that game, so it was really polished by the time we were done.

Other companies, it’s like one person, and they’re going to hire out and build a virtual team for any given project, and so you’ve got a collection of people that are kind of thrown together. And that’s not to say that people aren’t excellent, it’s just that it’s a very different experience and much more hands on. Although I would say that whether it’s a really big publisher with an internal team, or a smaller one with a virtual team that’s kind of brought together in real time, I’m pretty involved all the way down – like specifying when, you know, an apostrophe isn’t curly [laughs] – I’m looking at all the details there.

But it is a very different experience working with the bigger ones, the more established ones, and the smaller ones, which are scrappy – you have a little bit more control, I would say, in the smaller ones sometimes, because there’s just nobody else: someone’s got to step up and do the work. But I do really love working with teams of people who are far, far better than me. And sometimes that’s not always the case.

Are there ever any challenges where you’ve got your vision for how the game should be, but a developer comes in and says, ‘Well, that’s fine, but maybe we should tweak this and that’. Are there ever any hard lines from you: ‘no, this must stay the same’?

I can only point to one where I was frustrated, and it was probably my least successful game, where my vision for the way the components would work was very different from the way the publisher approached things. They were coming at it from a pure cost perspective, and I was looking at it and going: ‘This is going to go nowhere with this kind of level of quality’. I think they were just trying to market it based on the idea that it was inexpensive. And I’m like, ‘Well, this is just not gonna work’.

That was the only time really – I think I’ve been really happy across the board, very lucky across the board that the teams I’ve worked with have been really professional and brought a lot of value to it.

Well flipping that around then, I guess, what makes a developer especially effective to work with? When you sit down with a developer, when do you find yourself going: ‘Oh, yeah, that’s great. That’s really helpful’.

Yeah, I respond really well when things are data driven, like when they can point to playtests and say, ‘hey, you know what – these people are having these experiences’. It’s not just solutions. So I like to see data, sort of in context of play, from real humans. And then I like to see a tremendous amount of attention to detail tracking things down. I love it when people are brutally honest, but I also like things when they’re packaged up with, you know, soft communication – so it’s a little easier to swallow the pill [laughs].

That kind of package: really great insights, really good attention to detail, all founded on facts from real world play tests that are communicated well and tracked down – that’s what I’m looking for.

Can you think of anything specific in terms of, say, Fate of the Fellowship, that got changed through development that you hadn’t considered? Where you were suddenly like, ‘No, this is, this is a really good idea, actually, this does make sense’?

Yeah, I would say that there’s just thousands of micro decisions. When you’re looking at 13 characters, and 14 events, and 24 different objective cards, there’s just a tremendous amount of interactions. And you don’t want to be dealt the character and go like, ‘Oh, darn, I got that character’. You know? That they’re either less interesting, or perceived to be less powerful. So around the edges a lot of the characters got minor tweaks, or they might get a third, tertiary ability that doesn’t even get played sometimes in the game, but is a nice thing to have, and it has a little thematic twist. Some of the things Kevin cooked up really added a little roundness to characters and made them more interesting.

What does your own design slate look like in 2026? I think flickering stars is on BGG, but I haven’t seen anything else. Are we just getting the one this year?

[Laughs] I mean, like, knock [on] wood! That product’s been delayed a lot, so I needed to check with the publisher and find out what’s going on. My greatest hope is that it comes out this year. There are – let’s see, I’m looking over the whiteboard right now – at least one other product coming out in the Fall. I’ll set expectations for maybe two, and then I’ve got others in the pipeline.

I’m slowing down a little bit. The kids are out of the house, I’m enjoying travel more. So the whiteboard was full of games the past few years, and I’m just kind of letting that shrink a bit. But I will say I’m working on at least one legacy game with Rob Daviau. That’s been a lot of fun.

Flickering Stars looks to me like a bit of a departure from a lot of the stuff you’ve designed elsewise – and I do apologise, I don’t know much about it. So is this one that’s been bubbling around for a while now?

Oh, like eight to ten years. I’m not kidding! And [co-designer Josh Cappel] worked on this before I did for like, a couple of years. So it is, I think, easily the longest development time of any product I’ve ever worked on. This is also my kids’ favorite game. It’s a dexterity game where you’re flicking little spaceships across the table, and it plays a little bit like a miniatures game without the fiddly bits. Where you put your tokens on the table: position really matters, there’s a lot of strategy, but it comes off and looks like a pretty lightweight, easy to learn thing.

The challenge with these things is that it requires a lot of specification around the plastic components. There’s actually spaceships in here that will launch a projectile, another one that rolls a large steel ball across the table – really fun stuff. And you look at it, and you’re like, ‘I know how to play that’! [laughs] And it plays pretty fast, so it’s a really great package. It’s all done, as far as I can tell, they just need to print it and get it into distribution.

Why has it taken so long, do you think? Was this something that you showed to multiple different publishers over time?

It’s been a combination of all sorts of factors. I mean, I don’t know where to begin. It did see different publishers, and sort of went on a journey there. It found a home with Friendly Skeleton, formerly Deep Water, where they just adored the game – really saw the vision, were all in, and were great partners to do the product design etc. But then we had Covid in there, we had the tariffs, there was some restructuring with that company – it’s just a whole string of things. So we’ll see how it plays out.

You’re currently secretary of the Tabletop Game Designers Association – why is an organisation like that important within the modern board game profession?

Oh my gosh, it’s so important! If it did nothing other than contract review, it would still be very important. Game designers are vulnerable folks, right? We work with much larger publishers who have a lot more power in the relationship in many cases, a lot more leverage. I think, like for book authors or any creatives, musicians, etc, it helps if we can band together and look out for each other.

And so this organization provides all sorts of services for its members. I think one of the most important is contract review, where you can you can send in contracts, get them reviewed and make sure that you’re agreeing to terms that are fair and the industry standards: you’re not stepping on landmines and so on. But we also have a really active Discord community where you can talk with each other, you can share playtesting tips, network. It’s just a great place to connect with other people in the field.

So I was a member of SAZ – I’m not even going to pretend to say I know how to pronounce it – the German equivalent of the TTGDA, for probably about 10 years now, and joined them just for very similar reasons. But TTGDA is here in the States. It’s very present. We’re trying to meet up with people in various conferences and to provide lesson services for people within the field. I think it’s a really good bargain too! I mean, you’re paying about 100 bucks for a year, and legal fees just alone would be much higher than that.

So I jumped on it – when Geoff [Engelstein] announced that he was putting it together, I’m like, ‘That’s such a great idea’. And then he invited me to serve on the board, so I leapt on that.

Geoff is obviously a heavyweight within the board games industry. [TTGDA co-founder] Elizabeth Hargrave too, as well yourself. How important is having that kind of heft in the association, in terms of being able to talk to publishers on behalf of new designers, perhaps who don’t have that track record within the industry?

Yeah, I think it does matter to have some bigger names on there. I know that SAZ in Germany was actually headed by Alan Moon for a while, which is odd, him living in the States, but his name caught my attention for that. And similarly, I know Geoff has done just great work in the industry here, and I really wanted to help support him.

If you could change one standard practice in, for example, designer/publisher contracts or workflows, what do you think it would be?

Honestly? I kind of wish they were just a little bit more Lego-like, so you could just run through a checklist and go: ‘covered, covered, covered’. You can do it right now. It’s just the language across all the different contracts is presented differently. One of the contracts I had was a modified comic book contract that had been modified and modified, modified and modified over years and years, to suit the requirements for game designers. But it was just so weird – it was this weird Frankenstein’s monster that I had to go through and really kind of try to suss out the language in. And it’s difficult to know what’s missing, so you really do have to run through a checklist. So this is something we’re working on at TTGDA, just having a more standardized contract.

I have seen some that actually pull the terms out to the front so you get, like, a summary sheet, and then you see the boilerplate in the back, and it’s a lot easier to understand.

Here’s a very personal annoyance that I have: it’s really hard for me to get designer copies a lot of the time. I don’t know why this is with companies, but, like, I would like to get the product at least as soon as the public does. And sometimes it’s months before I get my stuff [laughs] It’s really rough. I would like to see it and play it and have it!

Matt, what you need to do is become an influencer, start a YouTube channel, and you can get those games immediately.

[Laughs] I guess so, maybe I could talk about it more that way: I’d like to support the game, but I need a copy first.

That is crazy, isn’t it? You’d think they’d be all about giving you a copy, because you’re in a prime position to promote the game and be excited about it, right?

And it’s not due to any kind of ill will or anything like that. It’s just, like, internal processes are sometimes screwy. And yeah, it’s not always the case. It’s just it’s especially jarring when it happens.

The sort of contract work you’re doing with TTGDA must be useful to some publishers as well, right, for similar reasons? I’m sure some publishers come to the contract side of things and they’re like, ‘man, we don’t know what we’re doing – I guess we just repurpose this comics contract?’, or try and come up with something that has a lot of legalese in, which feels like it covers them?

I would think it would be very, very useful. I think awareness needs to be higher, though – I’m not sure enough publishers are doing that. Because it’s there, you can take an off-the-shelf contract that we’ve got and then modify and suit your needs. And the way it’s set up is, like I said, very Lego-like – you can put together the different sections together and assemble one if you want to.

But, yeah, I think too many are just very green and just take a shot in the dark and hope for the best, and we see some really, really incredibly bad contracts. I can’t speak to this nearly as well as, say, Geoff and Elizabeth, who head up that side of the house. I’m sure they could tell you some really, really great stories.

I’ve been trying to get something lined up with both of them for a while now – I will absolutely try and make that happen this year. I wanted to ask: what’s something publishers should stop expecting designers to do, or to do for free?

I think you see this more with smaller ones, where I’m just asked to wear lots and lots of hats, whether it’s doing the final edit on the rule books or… I think we see this less now, but I was aghast in the past, when my prototype art was used, actually in the final product. Like, I’m responsible for the game design!

I would like there to be some sort of development support. Like, with Pandemic I had zero development support – it was published basically as I handed it over. [Z-Man Games founder Zev Shlasinger] was a one-person shop, and he did give one request, which was to have a few more roles in the box. But it was basically just like, you had to wear a lot of hats: creative director, art director, final proofer, all these different things. And I think it’s important for publishers to realize that we have a certain limited amount of time, and our role is game design. We still want the product to be as good as it can be. We’re probably the strongest advocates for that, and so we’ll step up and fill in gaps, because we want the final product to be really, really good, and it’s our name on the front of the box. So we need to do that, but there’s a certain limit.

So I guess one of my pet peeves is when I’m essentially asked to be the creative director, and I would like there to be someone else, even if it’s just a graphic designer who’s keeping an eye out and taking on that role. Maybe they have that formal role of creative director, but someone who’s, like, really responsible for the product at the publisher and not expecting the game designer to take on that role.

Do you think that’s improved, generally? Or do you think it’s improved for Pandemic designer Matt Leacock, more perhaps than for other people?

[Laughs] I don’t know, I really don’t know. I’ve got my own limited, narrow, viewpoint of the relationships I’ve got with the publishers I have, and I gotta say for the most part it’s been really, really good. And so I think it just stands out sometimes when you’re like, ‘oh, wow, it’s not always like that’, right? And I think the reality of it is, it’s a tough business, and if you’re a small company it’s difficult to hire a creative director, and you’ve got this game designer here who can take on that role. And I care about this stuff, so I’m gonna step up! I don’t want to blow this out of proportion, but it’s an annoyance sometimes. I think the products are so much better when you get someone looking within the company, ensuring that you know this thing’s gonna be really, really great.

So: if you were starting out as a first time designer today, what pieces of advice would you give yourself in order to sort of stand out and, like, build it up to a professional career?

I think a lot of it is the stuff that I’ve I had to learn on my own, and I’m not sure hearing it would really help. I would just have to do it. I fall into a lot of traps where I spend too much time trying to make the prototypes look good rather than play well, and I continue to do that [laughs]. So again, I could tell myself not to do that, but it’s something I just have to continually work at, because just many, many iterations with lots and lots of people are where you kind of get to quality.

And really, the play is the thing, that’s what matters in the long run. You can have a big hit that does well once and then goes out of print, but if you want that longevity, the play has really got to be in the game, and you’re only going to get that if you’re really iterating and working really hard and showing it to lots of people.

So I would probably just reinforce those lessons that I’ve learned myself, and I would hear them and agree with them, and then I wouldn’t do them [laughs].

You’re not the first person that I’ve talked to about this, and I’ve heard that before. You have people saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what it looks like. You just got to get it on the table…’

I mean that’s not true – it does matter what looks like! [laughs] But there is a limit. I have a tendency to pull out the laser cutter – because it’s fun to make stuff look really good! And it’s also a great way to procrastinate on the hard work of making difficult decisions and trade offs and, like, killing your darlings and all that kind of stuff, which is just not fun a lot of times. Or killing the project, you know! I’d rather make it look better and see if it plays again [laughs].

There must be some positive element beyond procrastinating to it as well, though, because otherwise you wouldn’t keep doing it! There must be some element of: it’s time with the game, crafting it and thinking about the vision. And perhaps by sitting with it and crafting it in this way, maybe that gives you the brain space to put it in different directions?

That is 100% true. And so I’m understating: investing too much time in making it look good is obviously a problem, but it does mean that you’re spending a lot of time with the components and the game on the table. It’s just you’re not, like, running the engine: you’re waxing the car. You’re not in it test driving it, you know, and banging it into other things to see if the roll bars are going to hold up, right? But that’s painful work sometimes. And it’s, you know – it’s more fun to polish the car [laughs].

2025 was obviously really volatile for many publishers, and presumably for designers too, given tariff changes and general worries about the economy, and how much money people have to spend on things like games. How much of that filtered through to you as a designer, or to other designers that you were speaking to last year?

Yeah, from what I hear it’s been pretty rough. You hear about the different companies going out of business, sometimes you hear about designers not being paid on time. Delays, and just the length of time seems to just be longer in general – so development times have kind of stretched out on my end. Games that have been promised to release in a certain year, that year slips more often than not now. So that’s a thing.

It was difficult to keep, specifically, Fate of the Fellowship, in stock. It’s been nice that there’s been so much demand, but it would be better if we could have them on the store shelves. I think more than anything it’s been the delays. And I would think that – and this is speculating on my part – I would think that publishers are gonna be less likely to want to take certain risks given how volatile things are, so maybe relying on lines that are more well established, rather than swinging for the fences with something really risky.

Presumably you’ve been speaking to publishers towards the end of the last year and already this year – do you get a sense of how are they approaching things for 2026? Like, are there different strategies at play and desires for particular types of game, or ‘size of box’ game – are you seeing those sort of discussions happening?

Most of what I could share would be second-hand, just reading online how people are more open to card games and so on that have a lower cost of goods, just because of the tariffs and so on. But I haven’t really had those conversations myself so much, with the projects I’m working on.

You talk about riskier games, and publishers maybe battening down the hatches and sticking to their knitting in terms of what’s been successful previously. Where would something like Daybreak sit? Because I think if you if you’d asked a couple of years ago ‘will this game be hugely successful?’, I think there’d be plenty of people who would have said, ‘well, possibly not’ – it’s a strong issues-focused, cooperative game, and perhaps doesn’t fit in the traditional mould of a modern eurogame. Obviously it was very good, and hugely successful! Do you think it would be more difficult to “pitch a Daybreak”, something a bit left-field, today?

Yeah, hard to say. I mean, [co-designer Matteo Menapace] and I were thinking it would be a tough thing to find a publisher, to some extent from the beginning, just given that it’s, you know, ‘let’s play a fun game about climate change’. It’s not necessarily something people are gonna want to sign up for, but at the same time there are a lot of eco-focused games, games about nature and ecology and so on. Wingspan really showed everyone that there’s a market for this kind of thing.

I think of [Daybreak] as a kind of a special case. We had the game, and they were looking for that game, and we just met up, and everything was great. So it’s difficult to know how that would have done back then, if we hadn’t found that relationship. And that’s as it was, much less with what we’re seeing now. Hard to say.

What design trends do you think are being overused right now, and which areas do you think are perhaps a little under explored?

Well, I don’t like to chase trends, so I think if your hot new idea is maybe a trick taker, you might be a little late to the party [laughs] There are so many of those. That said, there’s a huge built-in audience for those, and they’re really inexpensive to make. So, you know – I don’t want to dissuade anybody from chasing their dream, but I also don’t think you want to be chasing a trend that we’re actually seeing in the marketplace, given that it takes one to three years to get something out on the on the market.

Under-explored? Oh, God, I don’t know. That’s always the question, right?

Is it space-based flicking games?

[Laughs] 100% yeah, you really need to fill in your portfolio there. So many publishers don’t have a dexterity game. Here’s this wonderful game! Yeah. I’m not really sure. I’ll pretend that I know exactly what it is, and I’m not going to share it with you. [laughs]

Very wise, very sage! I do think more publishers should do dexterity games. I know perhaps it’s a difficult fit for their existing portfolio or style, but I play loads of dexterity games, they’re great, and it’s always fun, even if you’re bad at it.

Exactly, you can always blame your skill at flicking, not your strategy.

Are there any games in the past year or so that you’ve been particularly impressed with from a design point of view, where you’ve played it and thought, ‘oh yeah, that’s really craftily done’?

I’m perennially impressed and just blown away by [Reiner] Knizia’s work. The reworking of Beowulf that he did – and didn’t seem to go over well in the market – into Ego has been really amazing. He’s got three games with… I think it’s Bitewing: Ego, Silos and Orbit, and they’re all good, but I think Ego’s really something special. It’s got this great exploration into risk, and pushing your luck, and sunk cost and all this kind of thing – with really fun bits. Plays pretty snappily, and I think it’s just stellar design work.

And then I shelled out for the version of Quest for El Dorado, the international version with that art, and still adore that game. So those two just stand out in my mind. And a lot of the work by John D Clair, I think has been really fantastic. Those are the standouts for me.

Are there any mechanics you now actively avoid because of lessons learned from earlier titles?

[Laughs] No, I think mechanics are just, like, the tools you have in the shop. For me, it’s just all about: what is the game trying to do? And those are just the nuts and bolts that that you use to create those exciting changes in the game, to light up people’s brains. So I can’t think of anything specifically.

Well let me rephrase it then: is there any game you made previously where you thought: ‘I will never do that again’, for whatever reason?

Yeah, I would say that some of the dice games that I did, like Roll Through the Ages and Chariot Race, I think were fine for the time – but the downtime in those is just too high. I don’t think people have the patience for that sort of thing. So that would be something I would avoid. I think I would avoid games that just have a tremendous amount of plastic in them, for environmental reasons. So like, I’m looking at Era going, ‘Wow, that is a lot of plastic’. I have a follow up for that game that’s unpublished right now, and I don’t know what I’d ever do with it, because it just requires a metric ton of plastic. So I’m like ‘I don’t want to do that’ [laughs]. So those are considerations, not really mechanisms, so much.

Is there a structural issue in the board game industry now that you think needs fixing, but just isn’t getting discussed, or rarely gets discussed?

Oh, you’ve given me such a great platform for this, and I don’t really have a specific bone to pick right now [laughs]. There probably is. I mean, I’m concerned about the way that creatives are compensated, whether they’re illustrators in the wake of AI, or game designers just not knowing better and signing up for really bad contracts with exploitative publishers – or publishers that are just trying to make ends meet, and finding ways to whittle around the edges.

Has that been a big thing with within TTGDA? Members bringing you concerns about AI, especially on the art side of things?

I think there have been some discussions. I try not to get too heavily involved in them, because they tend to devolve into… it’s hard to change people’s minds online. I would say that the consensus is pretty much that it’s okay to use AI stuff for prototyping, but never in a final product, – at least our collective seems to have that mindset, I think? And even if you’re doing it in a prototype, there… I think I would just say some embarrassment about it. I’ve used AI in prototype art, and I don’t feel great about it, because I know it’s operating on the work of other people that’s been uncompensated. So I will probably think pretty heavily about whether it’s worth the squeeze there. If I can find other ways to do it, I think [it] would be do better.

It does seem to be creeping into more and more games. I don’t think many of the really big publishers have committed to using it yet, but we’re seeing it creeping in with some of the smaller publishers and individual creators. Is there some sort of inevitability about this?

I don’t think anything is inevitable here. I think as consumers we can say, ‘hey, we don’t stand for that sort of thing’. I’ve been kind of disappointed looking at the Terraforming Mars product line, and that publisher Fryx Games has just kind of embraced it unapologetically. And I’m like – I’m not gonna work with that publisher.

I feel like maybe there’s a certain justice element there that just really rubs me the wrong way. And if, as consumers and designers and media, we try to stand up for creators rights, then we can steer things a certain way. I still hold out a lot of hope for that, and I don’t think anything about it is inevitable.

Hi,

Is Matt aware of the existence of FlickFleet? Its a dexterity space game hand made by myself and Jackson Pope which his game sounds rather similar to.