How we made Wyrmspan: Designer Connie Vogelmann on creating 2024’s hottest game so far

Stonemaier Games’ big reveal of Wyrmspan – a new game “in the world of Wingspan” – last week might have descended like a dragon out of the blue, but it’s no surprise Elizabeth Hargrave’s hugely lauded 2019 design is getting a spiritual successor. Wingspan had sold over 1.6 million copies as of April last year – more than all of Stonemaier’s other games – including Scythe, Viticulture and Tapestry – combined. In an industry where selling tens of thousands of copies of a game is often seen as a success, those numbers are astronomical, and make it a no-brainer that more games based on Wingspan’s template would be in the works. The task of designing “Wingspan with dragons” was given to Apiary creator Connie Vogelmann – but as she explains in this Q&A interview, the new game is far more than just a reskin of its feathery predecessor.

BoardGameWire: How did the opportunity to design Wyrmspan come about?

Connie Vogelmann: The idea came from Jamey! He had been receiving requests for Wingspan spinoffs ever since the game was released, and a lot of folks throughout the years had requested a spinoff with dragons. Jamey and I had been working together for several months on Apiary by this point, and Jamey asked if I would be interested in designing a dragon-themed Wingspan spinoff (with Elizabeth’s approval, of course!).

Where did you begin with the Wyrmspan design – did the idea for the dragon theme come first, the

changes to the mechanics, or something else?

The dragon theme definitely came first, and came from Jamey as part of the initial discussion. The core concept behind the game was: how can we adapt the core system of Wingspan to make mechanical and thematic sense for dragons? We wanted to retain a lot of the engine-building elements from Wingspan, but create a new game with its own unique mechanisms that could stand on its own. Cave-building ended up being a big part of this; the idea of digging out caves and enticing dragons to live in them felt very thematic, and provided a good “starting point” to differentiate the two games.

Were there mechanical elements of Wingspan that Stonemaier decided must be kept, or did you have

free reign to change things up?

This wasn’t something we discussed in any kind of formal way, but Jamey, Elizabeth, and I all wanted the game to have similar engine-building elements to Wingspan. In addition, we wanted to retain the relatively friendly feel of Wingspan. For instance, none of us wanted a game where the dragons would attack each other, or where players could tear down others’ tableaus. Early prototypes of Wyrmspan tried to change up the “three-row” system of Wingspan. Several early prototypes of Wyrmspan had more flexible cave movement, in which players could build out caves in all directions, and/or move their explorer both horizontally and vertically. Ultimately, we felt that this system changed the feel of the game too much, and also ended up creating a lot of extra rules complexity without providing additional depth. With that in mind, we went back to the “three-row” system that was present in Wingspan, though there are some significant differences in the Wyrmspan player mats compared to those of its predecessor.

What was Elizabeth Hargrave’s role in producing Wyrmspan, and how did the two of you work

together?

I first met Elizabeth before Wingspan was released. We both live in the DC area, so often playtest games together. She played a big part in helping me playtest and refine Apiary, and has consistently encouraged and mentored me as a designer. In the context of Wyrmspan, Elizabeth provided advice and guidance throughout the process. First, she helped Jamey and I refine the initial concept, and the three of us worked together to identify how we wanted the game to look and feel. Elizabeth playtested Wyrmspan throughout design and development, and played a key role in troubleshooting problems. She also played a critical role in getting the feel of the game right. We wanted to ensure that Wyrmspan had its own identity, while still retaining some of the gameplay elements that had worked so well in Wingspan. There were a couple of playtests where Elizabeth essentially said: “this doesn’t feel enough like Wingspan,” so we worked together to figure out how to help Wyrmspan capture the feel and essence of Wingspan, while retaining its own identity.

How did you approach the problem of maintaining the success of Wingspan’s core design, while also

working in new mechanics and ideas?

This was probably the most challenging part of the process. During the design process, I tried a lot of different mechanisms, including several types and iterations of bag building (for action selection), several market mechanisms for buying or drafting resources, a bunch of different ways to build caves, different types and methods of cave exploration, and so forth. In a lot of cases, these new mechanisms ended up adding extra complexity to the game, and some added additional randomness as well. Taken together, many of these attempts made Wyrmspan feel like a very punishing experience: if you failed to suitably improve your bag for instance, you could fall far behind other players. Although Jamey, Elizabeth, and I wanted Wyrmspan to be a little more complex than Wingspan, none of us wanted this kind of punishing feeling to be in the game.

In my mind, the player mat in Wingspan is one of the critical elements that powers the game. Its fundamental innovation is that every single bird you play (no matter what the text on the card says!) improves its habitat. I think this gives Wingspan much of its identity, and helps every action to feel so rewarding. In designing Wyrmspan, we found that the more we departed from the structure of that player mat, the less the game felt like Wingspan. Once we decided to make the Wyrmspan player mat more closely align with the Wingspan player mat, we were better able to align the “feel” of the two games. Although there are some significant differences between the two games (which are discussed in more depth below), the core engine in the two games is similar – giving the two games an important shared foundation.

What was your thinking behind adding the need to excavate spaces on the player boards?

This was a part of Wyrmspan in some form or another from just about the first iteration of the game. It just made sense from a thematic standpoint that you would need to prepare an appropriate habitat for each dragon. In addition, the idea of preparing a habitat for a dragon, then enticing them to come live in it presents a wonderfully evocative mental image. Wyrmspan was always intended to be a little bit more complex than Wingspan, so from a mechanism standpoint, adding this additional sequencing puzzle was a good way to increase the complexity of Wyrmspan while still retaining many of the engine building components that make Wingspan enjoyable. As a designer, I am also a big fan of “instant” abilities, especially when these are incorporated into a system that also has engine building. Adding “when played” abilities to the cave cards presents players with some interesting sequencing and prioritization decisions (plus the instant gratification associated with an instant benefit!).

And what about the Dragon Guild track?

The dragon guild track was designed to solve a problem, and I think it ended up being a “happy accident” that significantly improved the game. In Wyrmspan, cave exploration occurs from left to right. This is the opposite direction from bird activation in Wingspan, which goes from right to left. Right to left activation allows you to have “half-steps;” on the Wingspan player mats, each additional bird you place into a habitat essentially gives you half of an extra resource. For instance, in the forest, the first space gives you one food, the second gives you one food (with the option of discarding a card to gain a second food), the third space gives you two food, and so forth. As soon as the movement switches from left to right, those “half steps” become almost impossible. Going all the way to full steps meant that players’ engines were taking off too quickly, and players became inundated with resources by the midpoint of each game. Making everything cost more wasn’t a viable solution; it’s not only clunky, but it made it difficult for players to get their engines going (which is hardly a fun experience).

What we ended up doing to solve this problem was re-working the resource economy in two ways: by adding eggs to some within-row benefits, then increasing the number of eggs that were spent throughout the game, and by adding the dragon guild. The second space in each row gives players an advancement on the dragon guild. The guild gives players a way to get resources that do not (necessarily) match the benefit associated with the current cave their adventurer is exploring. For instance, the adventurer might be exploring the Crimson Cavern (associated with food), but advance on the dragon guild to gain a dragon card. This de-syncing of benefits added an extra layer of strategic depth to the game, and added some interesting sequencing puzzles. From there, as the dragon guild was further refined, we added the idea of specific dragon guild tiles.

Most spaces on the circular dragon guild stay the same from game to game, but the juiciest benefits (associated with the top and bottom space of the track) change each game, and depend on the specific dragon guild tile that is placed in the center of the track. This adds an extra element of player interaction, too: spaces on the dragon guild tile are limited, and can be very strong. Having a different tile in play each game also adds variety and replayability to the game, as each tile changes the resources and benefits that are available to players.

How will dragon personalities and hatchlings work within the game, and what effect does that have on

player strategy?

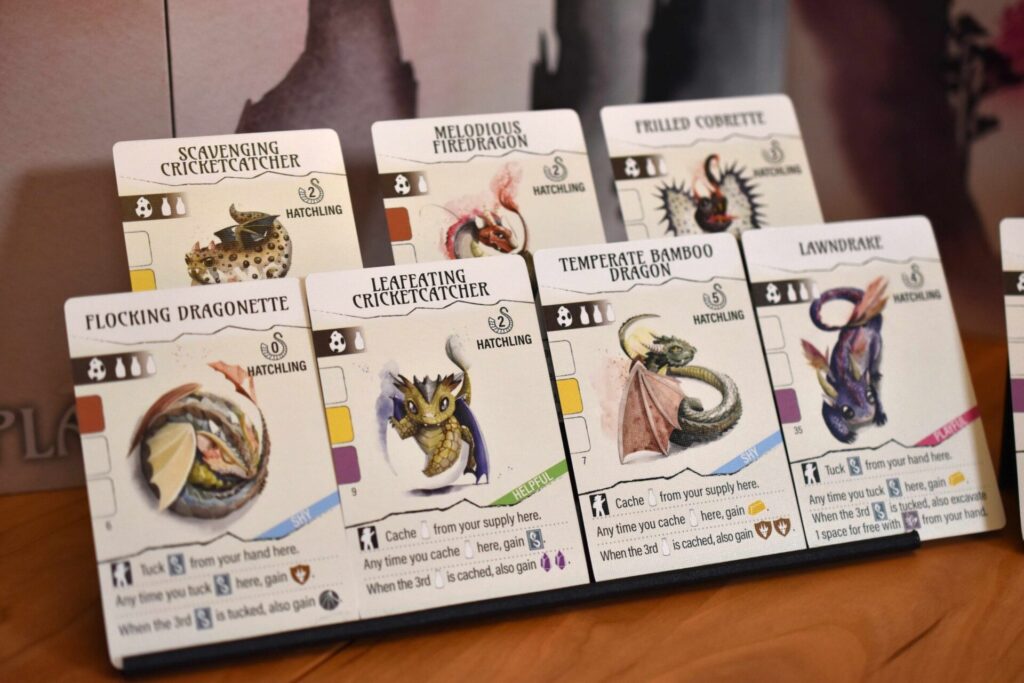

The hatchlings are some of my favorite cards! They make up about 20% of the dragons in the deck. Playing a hatchling is expensive; they require you to spend an egg as well as some milk to play them (you are hatching a baby dragon, after all!). After it has been hatched, each hatchling wants one of three things: more milk, meat, or friends (tucked cards). Whenever you give it one of the things it wants, it gives you some kind of a small reward. In addition, whenever you have fed a hatchling a third time, the hatchling gives you a bigger one-time benefit, representing the hatchling growing up! Hatchlings provide an interesting strategic puzzle to the game; if you are going to play a hatchling, you really need to commit to getting that third activation. They’re also some of the most visually stunning cards in the game – [artist Clementine Campardou] did an amazing job giving them all a ton of personality.

All adult dragons come in one of three sizes (small, medium, and large), and all dragons (both adults and hatchlings) have one of four personality traits – aggressive, shy, playful or helpful. These all have minor gameplay impacts; some dragons want to be near specific types of dragons, others want to avoid them, and so forth. In addition, similar to Wingspan, certain “if activated” dragons have abilities that draw cards from the deck, and resolve differently depending on the characteristics of the card that is drawn.

Are many of the dragon cards based on existing Wingspan bird cards, in terms of powers? Where do they differ, and what was the process for balancing such a large number of dragons?

All of the dragons in Wyrmspan are unique, and none are directly based on Wingspan bird cards. Although some of their core abilities (gaining food, cards, or eggs) are similar, both the economy and the underlying resources present in Wyrmspan are different than those in Wingspan, so cards aren’t interchangeable and wouldn’t function in the other game. A lot of the card design process was done through trial and error. The target number of dragons in Wyrmspan was 180 dragons, so I worked backward from there. I developed a rough estimate of how many dragons should fall into each category – e.g. “if activated,” “when played,” “once per round” and “end game.” I also estimated how many dragons I wanted to either use or provide each type of resource in the game. Then from there, it was a lot of trial and error.

Did any ideas from Apiary make their way across to this design? Or ideas you had for Apiary which

didn’t end up working for that game?

There isn’t anything direct – the two games have different enough cores and action selection systems that there wasn’t anything that I pulled directly from one game to the other. (From a timing standpoint, Apiary was also in its final development before work on Wyrmspan began.) That being said – friends who have played both games have almost universally told me that there are some significant similarities between the two in terms of how they feel to play. As I noted above, when I play games, I really enjoy instant abilities, and really enjoy interesting sequencing and timing puzzles. These elements have definitely made their way into Wyrmspan!

Was Dune Imperium something you looked at, given the recent release of Uprising as an expanded

version of the original base game?

Game design work on Wyrmspan finished up last spring, so Uprising wasn’t in the picture as we were working on Wyrmspan. That said, I think it’s important to differentiate Wyrmspan here, as I think Wyrmspan is quite a bit more distinct from Wingspan than Uprising is to its predecessor. Wyrmspan was built ground up as a new game, and is not compatible with Wingspan. Wyrmspan also introduces new gameplay elements that were not in Wingspan, and takes away some elements that were in Wingspan (like the dice tower and bonus cards). Although Wingspan and Wyrmspan are both built off a similar core system, I do think the two games feel quite distinct to play. I highly recommend that folks who are interested in Wyrmspan but who may be concerned about its similarities to Wingspan check out the materials that Stonemaier has published. They have made the rulebook available on their website and on BGG, and have also put together an FAQ that outlines some of the key differences between the two games. Jamey has also uploaded two relevant videos to Youtube: one shows 3 Quick Turns of Wyrmspan, and another outlines Key Similarities and Differences between Wingspan and Wyrmspan.

How long was the design process – when did you begin working on the game, and what stages can you

pick out, eg. prototyping, playtesting, etc.

We started the brainstorming process in January of 2022. I started prototyping and playtesting in February. The core for the game was reasonably far along by August of 2022, and Stonemaier did six or seven rounds of unguided (“blind”) playtesting between August and February of 2023. Game design and development was finished in March. The art was largely created simultaneously with game design and development, so there was a pretty quick turn-around between when the gameplay was finished and when the files were completed and sent off to the manufacturer. All-in-all, Wyrmspan will take almost exactly 2 years from conception to when folks will receive their copies.

What’s your favorite thing about the game’s design that others might not notice?

Favorite might not be quite the right phrase, but I do think there is one relatively significant difference between Wyrmspan and Wingspan that hasn’t been discussed. Specifically: in Wyrmspan, each time you enter a cave within a given round, the cost to enter that cave increases. The first time you enter that cave, the cost is a coin (essentially, one action point). The second time, the cost is a coin and an egg; the third time, the cost is a coin and two eggs. You may not enter the same cave more than three times within the same round! This seemingly small rules change has big impacts to gameplay! It not only forces players to build out multiple caves, but also creates a really interesting sequencing puzzle, and forces players to think hard about when to enter each cave!

Wyrmspan will be available from the Stonemaier Games website from January 31, with a worldwide retail release planned for late March.

[…] Wyrmspan, the dragon-themed successor to Stonemaier Games’ bestselling board game Wingspan, topped the charts for most new owners on BoardGameGeek last month after a huge launch campaign. […]

[…] kicked off 2024 in style with the surprise announcement of Wingspan spiritual successor Wyrmspan at the start of January, and revealed it had printed a hefty 100,000 copies for what was its […]